Lets talk about insurance

From the shocking hit on UHC’s CEO and the resulting nationwide backlash, to the waning days of open enrollment, insurance is having its moment right now - and it is not a good one.

Despite having worked in healthcare for almost a decade and a half it is surprisingly easy to forget how ubiquitous health insurance is.

At check in for a routine procedure I had done this week I was first asked to sign a statement saying “I agreed to pay whatever my insurance did not cover”. Being asked to sign this statement wouldn’t be out of the ordinary were it not for the fact that I was paying for the procedure out of pocket (cash).

Ironically, insurance has become the default form of payment throughout much of healthcare. And while its utility shrinks more and more each year it is so engrained in our system that even our cash pay flows still feel its presence (and respectfully, why spend resources designing a separate flow that historically is rarely used).

When I originally planned this post I had intended it to explore the wildly expensive world of self-funded insurance through the exchange marketplace. However given the recent events surrounding the untimely death of Brian Thompson, the CEO of United Health Care, and the resulting public outcry it only felt right to dive deeper into one of the most divisive and critical issues facing our country - health insurance.

What is health insurance?

In theory - health insurance is no different from any other form of insurance. You are trading a small guaranteed loss (your premium), for protection against an uncertain future loss (like a huge hospital bill). Historically we have seen insurance cross industries with a high degree of fidelity to this core principle of trading small certain losses for protection against unknown potential future loses.

The mechanism by which insurance companies work is through studying the probability of the insured event, then spreading risk and cost across large pools or people. Take car insurance for example.

On average ~5% of auto policies have a claim in a year. Geico can take those odds, along with the average claim cost and back into how much to charge for premiums so that they can be both competitive and profitable.

Importantly, this not only makes business sense but it makes logical sense. Most individuals couldn’t afford to replace their car or pay significant medical bills if they were injured in a wreck so it is prudent to give up a small known amount to guard against this larger loss. The same applies to home insurance - $1,000 a year to guard against losing your $350K house - a universally prudent decision.

In fact when you look at almost any type of insurance you see a very consistent theme in the risks which they guard against. Namely that they are infrequent, unpredictable, and well defined.

The one insurance product where this does not apply? Health insurance

In many ways health insurance is not insurance at all, it in fact is the antithesis. As my accountant reminds me every tax season “the only place I want you to lose money every year is on insurance - it means your house didn’t burn down, you didn’t get in an accident, you were healthy, and you didn’t die”.

Ask anyone around you “do you plan to use your car or home owner insurance policy this year?” and you’ll get a weird look and a resounding “No”! But ask them if they plan to use their health insurance this year and most will probably tell you they already have.

One of the primary problems with health insurance is that it has been co-opted into a de-facto protection plan, like a slimy used car warranty or the $6.99 protection plan for your $9.99 toaster from Walmart. A simple rule of thumb is if you plan to use the policy- it is not insurance.

A reasonable person might ask why has health coverage failed to conform to the standards of insurance, and indeed that is a topic worth exploring.

How did we get here?

History is a record of ''effects" the vast majority of which nobody intended to produce.

Joseph Schumpeter, 1938

It should come as no great surprise that our modern health insurance system was not planned but merely an unintended collateral consequence of other decisions.

In the earliest days (we’re talking 1800’s) health insurance did not cover any medical payments, it’s primary purpose was to cover lost income from an inability to work due to sickness. Given the primitiveness of medicine at that time which largely centered on containing the spread of contagious disease and snake oil remedies - it made sense there was no going concern for how to make medical payments because they didn’t exist.

While it is generally agreed that the first modern insurance plan was formed in 1929 between Baylor University Hospital and Dallas public school employees (later given the name Blue Cross), it was not until more than a decade later that widespread adoption of private health insurance took off.

The year was 1943 and we were deep in the throws of WWII. As a part of the wartime economy strict wage and price controls had been introduced in the US. In an economy already short on labor wage caps made it even more difficult for companies to attract talent. The body that set these restrictions however (the aptly named War Labor Board incase you are wondering) did not consider expenses for insurance as a wage expense.

The result was employers, desperate to attract workers, adding health insurance as a benefit. Employment based insurance was further bolstered in 1954 when the IRS clarified that employee health insurance expenses were tax exempt - incentivizing employers to offer insurance as a lower cost way to compensate employees than straight cash.

This was the first misstep - tying healthcare to an arbitrary, and often transient arrangement like employment.

As healthcare services expanded and medicine became more advanced what was once a fringe, rarely used benefit, gradually became a large cost center. Whats more, because insurance abstracted those costs (ie. a $5 copay for a $150 doctor visit), the person consuming the service was woefully unaware of what the service actually costed.

This lead to vast amounts of over consumption of healthcare due to a phenomenon known as moral hazard - when an insured party behaves differently than they would if not insured. This is a topic we will discuss at more length in the next section but importantly this detachment between the person who pays for a service and the person who receives it resulted in massive price inflation.

Why healthcare makes a horrible insurance product

At the outset I discussed how health insurance does not conform to the general principles of insurance. So why don’t we just make it conform? Well, much like your relationship status on Facebook - it’s complicated.

Healthcare is DEEPLY personal and often indelibly consequential. Deny someone their water back up claim and sure it sucks but life goes on. Deny someone’s request for chemo or a surgery and quite literally their life might not go on. Yet, no matter how heart wrenching healthcare is the laws of economics know no exceptions.

It is this duality - being bound both by the expectation of compassion and the principles of economics and risk - that makes health insurance so menacing.

Take the basic actuarial principle of moral hazard- which is described in the excerpt below:

“In its most traditional usage, moral hazard is identified with an increased probability of loss due to various kinds of unethical or imprudent behaviors on the part of an insured individual. These behaviors include extravagance, malingering, indifference to accident avoidance, claims fraud, dishonest failure to disclose a known hazard as part of an application for insurance, and imprudent failure to purchase insurance until the hazard is at hand (e.g., one's house is burning down).”

Then take the following set of exclusions for common types of insurance:

If your house is currently on fire you are not eligible for property insurance coverage

If you are a smoker with a history of 3 heart attacks you are not eligible for life insurance

If you have had 5 accidents in the last year your auto insurance premium will be extremely high or you will be ineligible for renewal

And then consider similar statements but tweak them for how health insurance actually works:

If you have a pre-existing condition we will cover it, and at no additional expense

If you engage in negligent behavior (sedentary lifestyle, poor diet, alcoholism, etc) we will still cover claims resulting from that negligence

If you had $100,000 in medical claims last year we will charge you the same premium next year as the person who never saw a doctor once

Or to really drive the point home take the health insurance logic, but apply it to any other other insurance product:

If your house is currently on fire we will issue you insurance to cover replacement.

If you are a smoker with a history of 3 heart attacks we will sell you life insurance at the rate of a healthy person your age.

If you have had 5 accidents in the last year we will renew your auto coverage and not raise your premium

If the last set of statements were true, we would see the same moral hazard in other insurance industries that we do in healthcare. People wouldn’t buy car insurance preemptively, they would buy it after the crash. They wouldn’t worry about buying the house that is about to fall over - they would just file a claim.

It becomes immediately clear that healthcare is not an insurable product. Not because it cannot be, we certainly could apply typical underwriting standards, but because we don’t want it to be…and that is a good thing.

A State of Upheaval

This week we saw the undercurrent of tension in healthcare come to a head. Regardless of your view on the state of our health insurance system no person deserves to lose their life in that fashion and I feel for the family, friends, and colleagues of Brian Thompson.

As someone who’s entire career has centered around healthcare I know full well the tale of two cities that has been playing out for decades. Even so it was no less shocking to see the overwhelming response of rage from vast swaths of Americans in light of the recent events. And while it would be easy to dismiss the sentiment expressed as reprehensible or juvenile that would only be further missing the point.

For those who must get their insurance through the exchange like myself (primarily self employed individuals) there is no time of the year that more poignantly reminds us of how broken our health insurance system is.

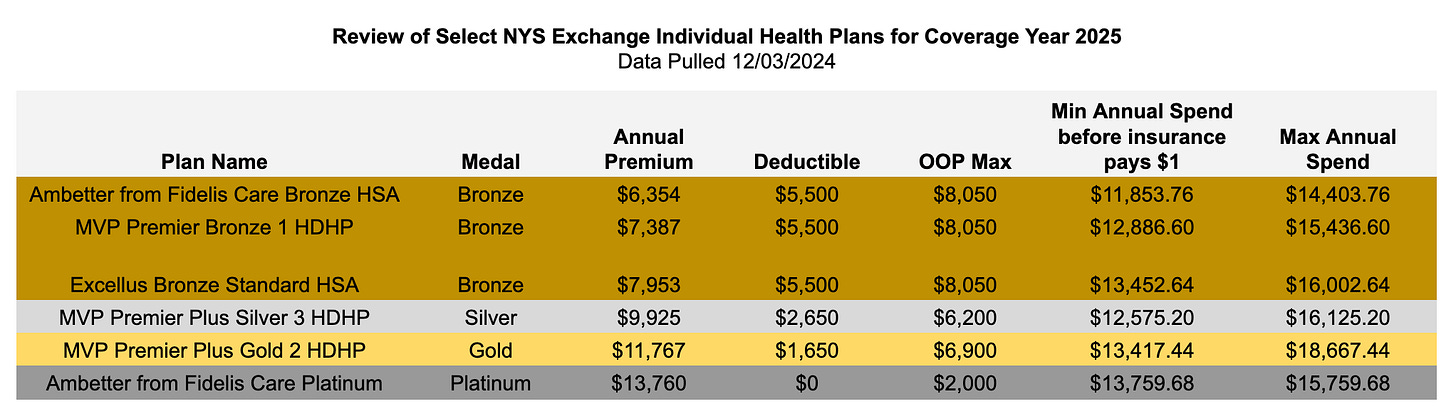

As a healthy 33yo, lifetime non-smoker, who takes no meds, and consumes almost no healthcare in the average year, these are the BEST options I have for health insurance for 2025:

Busy table - I know. Let me give you the highlight.

The cheapest HSA eligible plan in my zip code will cost me in excess of $6,000/yr in premiums, plus another $5,500 in deductible spend. That means I will pay no less than $11,853 (remember there is healthcare that insurance doesn’t cover so that number is likely to be more) before my insurance contributes anything towards care.

Five figures is a high price to pay just for the “benefit” of having insurance - even more so when you consider the fact that to qualify for medicaid in NYS (insurance for low income individuals) as an individual you must make less than $20,784. Is it any surprise that such angst exists when someone making $21,000 could be on the hook for $12,000 in healthcare expenses before their insurance pays a dime?

Whats worse is the is just the ticket to the dance- we won’t get to dive into the world of prior authorizations, formularies, and restrictive networks which limit the ways in which individuals can receive care.

Where do we go from here?

The resounding question at this point is no longer “what is broken with our system?” but “how do we fix it?”

Health is complex and health insurance bears those same complexities. Every health insurance model created to date has its draw backs and so it becomes a matter of finding best practices for a given population.

Call me biased (I was the first employee at Ro) but I have been encouraged by the recent move to more direct to consumer health offerings. Reconnecting payor and patient is a critical first step in commoditizing care where appropriate.

In a similar light seeing the rise of direct primary care has also given me hope we are on the right path as the care provided is often much more holistic in nature with an emphasis on prevention.

Above all else though what restores my faith is that there is an increasingly large segment of the population who cares deeply about personal health and is making the investments in food, exercise, and socialization to simply require less healthcare over the long run. We are questioning everything and demanding answers to questions we previously were told had already been answered (like is red meat bad, is cholesterol actually the widow maker molecule, and should we really not feed peanuts to kids till 3 years of age?)

As the adage goes an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. So while we have much work to do fixing our health insurance system, if history has taught us anything it is that meaningful change always start with a frustrated and motivated group of individuals using that energy productively.

Sometimes, after receiving healthcare services, I ask "What's the cash pay amount for that CPT code?" Often, the answer is HIGHER than the insurance-negotiated rate, which makes no actual sense. I just offered to eliminate all your overhead in this transaction, and you quoted me a higher price. Things are indeed broken.